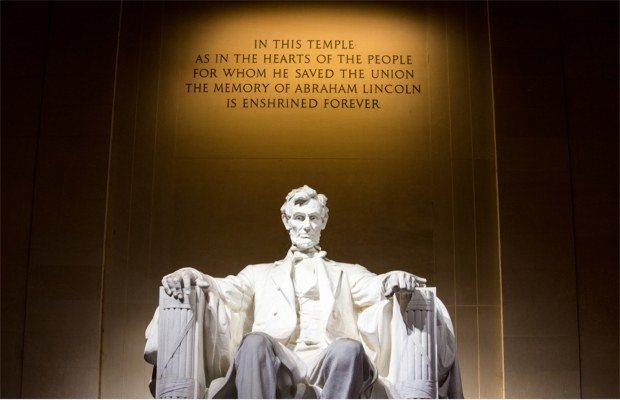

What follows is a brief history of Abraham Lincoln, a humble effort to objectively summarise the life of an extraordinary and complex man in fewer words than can suffice. Ideally, it will serve to inspire further investigation and scrutiny.

Lincoln was born in a log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky on 12th February, 1809. He was the second child of Thomas and Nancy Lincoln.

During Lincoln’s early childhood, on at least two occasions, the family was forced off the land his father had bought or leased due to property title disputes. As a result, Thomas Lincoln decided to relocate to Indiana and settle in virgin forest.

Thomas and Nancy Lincoln upheld highly restrictive religious values. This may have had an adverse affect on Lincoln’s own religious beliefs – he never joined a church and was possibly an agnostic. However, he did invoke the almighty in letters and speeches; he could quote from the bible like a cleric; and he attended church services with his wife. One value he did share with his parents was an abhorrence of slavery.

Lincoln’s youth was marked by tragedy – as was his adult life. His brother Thomas died in infancy; his mother died of milk sickness in 1818; and in 1928, his elder sister, Sarah, died during childbirth. The death of his sister was particularly devastating for the young Lincoln.

His father remarried a widow, Sarah Bush Johnston, who formed a close relationship with young Abraham.

Lincoln’s formal education was irregular and may have amounted to less than one year of tuition in total. His commitment to self education gave rise to the belief that he was lazy and inclined to avoid work. Even so, he grew into a tall, athletic youth, and became a skilled axeman and formidable wrestler.

The young Lincoln sculpture – Senn Park, Chicago.

Shortly after the his family moved to Macon County, Illinois in 1930, Lincoln left home and settled in New Salem in Sangamon County. In 1832, he and a partner purchased a small general store on credit. However, the business was not successful and Lincoln soon sold his shares after deciding to campaign for a seat in the Illinois General Assembly.

His gift of language and ability to conjure up anecdotes made him an instant crowd pleaser. But his campaign was interrupted when Lincoln briefly served as a Captain of the Illinois Militia during the Black Hawk War.

He returned to the campaign trail after his military service and contested the August, 1932 election for the Illinois General Assembly. Although overwhelmingly successful in the New Salem Precinct, Lincoln finished well out of the running for the four available seats.

While working as a postmaster and county surveyor, he decided to become a lawyer. He studied privately – without tuition of any sort – and at the same time campaigned again for election to the Illinois General Assembly. He was elected in 1936 and went on to serve four terms as a Whig representative for Sangamon County. He was admitted to the bar the same year and moved to Springfield, Illinois to practice law.

Lincoln was a very successful lawyer – a daunting adversary and highly persuasive advocate. To his clients he was ‘Honest Abe’, a nickname remembered to this day.

In 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd, a well educated woman from a wealthy family of slaveholders in Lexington, Kentucky. They had four sons, of whom only one survived to adulthood. The death of their sons deeply affected both parents. But Mary suffered from clinical depression and was briefly committed to an asylum a decade after witnessing her husband’s assassination.

Having promised to serve only one term, Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846, the only Whig from Illinois. He loyally toed the party line. However, the party was soon to become irredeemably divided over the issue of slavery.

Lincoln was as good as his word and returned to his legal practice after a single term in Congress.

Although legal throughout the south, slavery had been outlawed in all northern states since the beginning of the nineteenth century. Lincoln opposed any effort to support the spread of slavery into new territories being established in the west.

The regressive Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854) empowered settlers of new U.S. territories to decide locally whether or not to permit slavery. This new development forced Lincoln out of political retirement. He would not accept that a nation, founded on the principle that all men were created equal with inalienable rights, could tolerate the spread of slavery. It was increasingly clear to Lincoln that rather than gradually becoming obsolete – as it already was in the north and most of the enlightened world – slavery was gaining new traction in the United States.

Lincoln ran unsuccessfully (as a Whig) for election to the U.S. Senate in 1854. However, his ‘Peoria Speech’ was to set the tone for his presidential campaign. He believed that the Kansas–Nebraska Act had “a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself; I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world.”

In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court issued the infamous Dredd Scott decision which held that African Americans were not and could never be citizens of the United States. The court decided that Dredd Scott, a slave residing in a territory where slavery was prohibited, was not entitled to his freedom or to constitutional protection. It further held that the Missouri Compromise (1820) – which declared that all territories west of Missouri and north of latitude 36°30′ would be slave free – was unconstitutional.

Lincoln condemned the Supreme Court decision, insisting it was part of a conspiracy to extend slavery. However, the Whigs were split on this issue and on the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

The Republican Party was formed by disaffected Whigs dedicated to the antislavery movement. Lincoln was a leading influence on party policy.

The Republicans nominated him as a candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1858. During his campaign, Lincoln engaged in the celebrated Lincoln–Douglas debates and delivered his famous ‘House Divided’ speech inspired by the Gospel of Mark. His enduring remarks form the speech are:

“A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

Lincoln did not win election to the Senate but he did become a leading, national political figure. At the 1860 Republican National Convention, Lincoln was nominated as the Republican Party candidate for the presidency.

He was elected on 6th November, 1860 despite the fact that he received no support from slave-holding states.

Secessionists immediately implemented plans to leave the Union before Lincoln’s inauguration in March. By February, 1861, six states — Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas — seceded from the Union, adopted a constitution and formed the Confederate States of America. Jefferson Davis was elected to be its provisional president.

Incumbent President Buchanan and Lincoln both declared the Confederacy illegal. However, Lincoln did attempt to assuage the concerns of Southern States in his inaugural address when he declared:

“I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

A failed peace conference in 1861 made it abundantly clear that the leaders of the Confederacy would not rejoin the Union under any circumstances. Yet, the Republican leadership were equally determined that secession would not be tolerated.

The Civil War commenced when Confederate forces attacked Union forces at Fort Sumter on 12th April, 1861. Lincoln called on all states to send troop detachments to defend Washington and “preserve the Union”. Forced to choose sides, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas also seceded from the Union.

When Union forces moved south to confront the rebellion, mobs in Baltimore, Maryland attacked Union troops and damaged critical railway infrastructure. Local officials were arrested and Lincoln conditionally suspended the writ of Habeas Corpus.

With congressional approval, Lincoln made unprecedented use of his presidential war powers. After suspending Habeas Corpus, he initiated the blockade of Confederate shipping ports, allocated funds prior to Congressional appropriation and arrested people suspected of having Confederate sympathies.

Lincoln painstakingly micromanaged the war to the extent of personally monitoring telegraphic communications and comprehensive aspects of the Union war effort. The north expected a swift victory. It didn’t happen.

General Robert E. Lee’s forces crossed the Potomac River in September 1862 and the Battle of Antietam ensued in Maryland. The Union prevailed but the battle was bloody and losses were unprecedented. However, it empowered Lincoln to announce that he would issue an Emancipation Proclamation the following January.

As the war dragged on, support for the Republicans waned in the 1862 midterm elections. In the major cities conscription, reports of horrific casualties and a perception of corruption implied by the extreme and extended use of presidential war powers were aggravating factors.

In May, General Hooker was routed by Lee following the Battle of Chancellorsville. Hooker was replaced by George Meade who followed Lee into Pennsylvania to engage Confederate forces at Gettysburg – it was to be a game changing Union victory.

In June 1862, Congress passed an act banning slavery on all federal territory.

In July, the Confiscation Act of 1862 also passed. It provided for procedures that would free any slaves owned by people guilty of aiding the rebellion. Lincoln approved the Act as a matter of principle but doubted its legality.

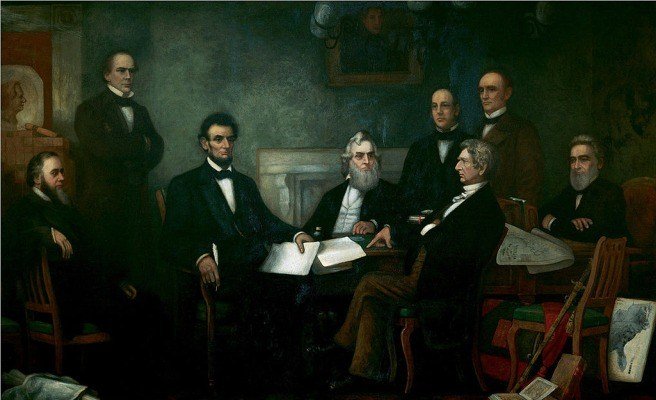

On 1st January, 1863 Lincoln issued The Emancipation Proclamation “a fit and necessary military measure”. It freed all slaves held on Confederate lands in perpetuity. Vocal anti-war Democrats argued that the proclamation was an obstacle to peace. But Lincoln insisted that despite his personal objection to slavery, his primary duty as president was to preserve the union. He wrote:

“If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

By the end of the year, twenty regiments of liberated slaves from the Mississippi Valley were recruited into the Union forces.

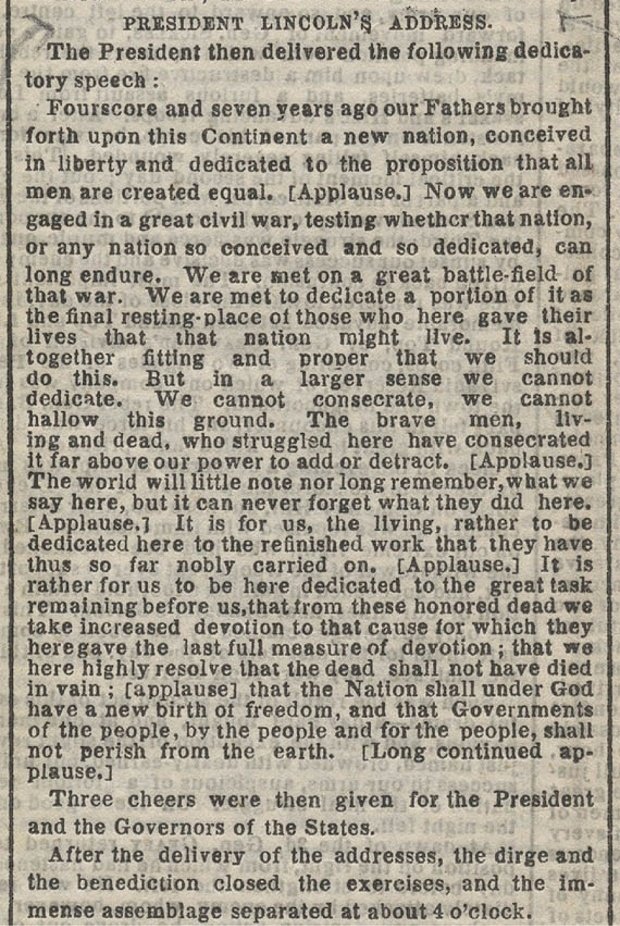

On November 19, 1863 Lincoln delivered his most famous speech – The Gettysburg Address.

General Ulysses S. Grant’s was given command of the Union forces in On 2nd March, 1864. His victories at Shiloh, Vicksburg and the campaign that followed had been too impressive to ignore, whereas General Meade was criticised for his lack of progress and failure to capture Lee’s forces as they retreated from Gettysburg.

Throughout 1864, Grant waged a war of attrition knowing that Lee’s forces would be diminished by every battle. Lee moved south and Grant followed, destroying Confederate infrastructure along the way.

Peace negotiations initiated by the Confederacy stalled as did Grant’s progress in the south, and appalling casualties without any sign of a comprehensive Union victory threatened Lincoln’s re-election prospects. Lincoln reinforced Grant and unified Republicans in support of the command.

Following the capture of Atlanta and Mobile by Union forces, the pressure was once again on a deeply divided Democratic Party, and Lincoln was re-elected on 8th November.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution to abolish slavery was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House on January 31, 1865. It was ratified by the required number of states and adopted in December that year.

Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth 14th April, 1865, five days after the surrender of Robert E. Lee. It was Good Friday.